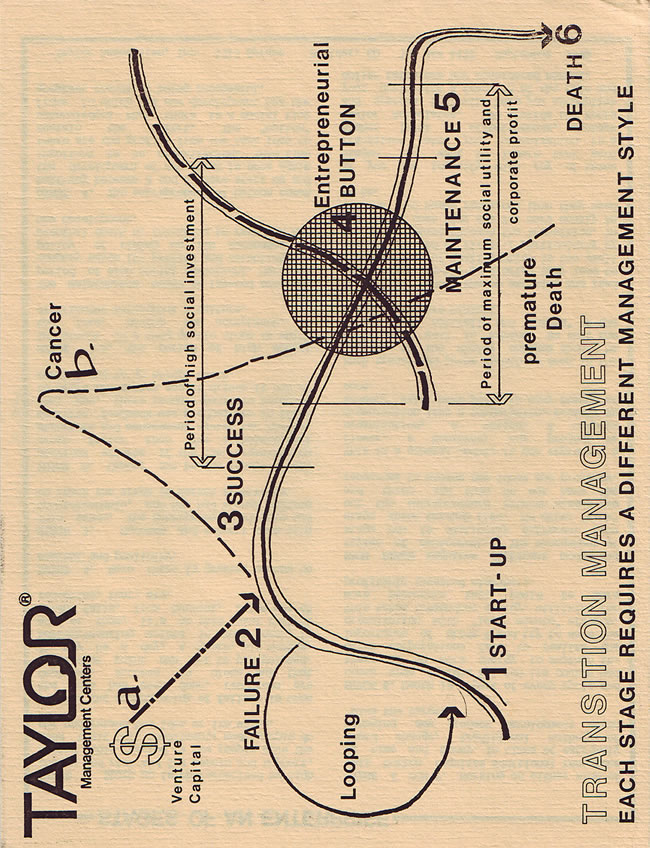

Boulder Anticipatory Management Center |

1982 Marketing Piece and Related Start Up Stories |

posted:

January 14, 2008 • revised December 28, 2010 @ Elsewhere |

FIRST USE |

DESIGNING THE DOCUMENT |

| This is the print media piece that we used in our startup years to explain what we were doing. It was not a mail out. We would verbally walk a person through it and then leave it with them as an aid when s/he talked to others. |

| This version of it was the last printed just prior to our sale to the Acacia Group. It had actually changed little since the first draft from the year before. How this came about is one of our best “founding” stories which I believe has great relevance today. |

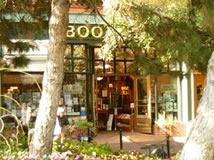

| When Gail and I moved to Colorado we know three people in the entire state. I went to work for a landscape company doing design, carpentry and field supervision. Gail started networking in the Boulder area finding out what was happening. This lead to a relationship with the head of the city HR department which lead to City Manager Commissioning the Boulder Affordable Housing project [link: boulder affordable housing project]. Through my work, I became friends with the architect who designed the Boulder Mall and it so happened that he had a 3,000 square foot space, which he and his partners were keeping for future expansion, in his building a block off the Mall. The open space was nicely finished out in every regard just waiting for use. We were able to design our WorkWalls and furniture, fabricate everything and get operational in a couple of weeks. |

| We our first Center just-in-time to do the DesignShop for the Affordable Housing Project. We did it with a little cash and a whole lot of credit although, because of the state of the space and we did most of the work ourselves, this cost was not high. Our first Workwalls and many furniture pieces where all all hand built, mostly in the environment. We ended up with a great place to work, and a show case - for a song. Because the Affordable Housing Project was a key public-private initiative many civic, business and government leaders were involved and came to the event. In a 30 day period we prototyped our first environment and demonstrated our work method to community leaders. This DesignShop - our first - launched what is today MG Taylor. |

| Over a two year period, the basic Taylor Method was conceived, developed and practiced. We attracted clients from across the United States. Acacia bought us because they wanted our full attention for several years and this provided us our first opportuinity to facilitate the transformation of a major company from end to end. In between our beginning and Acacia, however, were some lean times. |

| One Friday afternoon, in 1981, Gail and I found ourselves sitting in the AMC facing our first real crises. A friend, mentor and board member had just left. A successful and semi-retired entrepreneur, she had just refused to make an investment in our enterprise. While supportive, she said that “things were just not right” but could not articulate what was to her the barrier to making an investment. We had a few dollars in our pocket, a quarter of tank of gas, no money in the bank and two months of office rent due the following Monday. Gail and I drove up the Flatirons to our mountain cabin, gathered up the cat, what food we had and drove back to our work environment. We had our space, our tools and the determination to find an answer by Monday and execute it by the the late afternoon follow on meeting we had scheduled with Meg. To fail to do this, we felt, could trigger the premature death of our nascent enterprise. |

| We determined that although our work was growing nicely we did not have a sufficient base to keep a 3,000 square foot environment and 4 people (including us) employed. We also realized that we were not adequately explaining the premise of our work. We needed to get to more people and we needed to define the issues we wanted them to focus on - not just help them solve problems from the vantage point of their existing paradigm. |

| By noon Saturday we had designed the first Invitational DesignShop® structured around the issue of productivity. An Invitational allows each organization to send five people to the event allowing several different groups from business, government, academia and NGOs to focus on a common problem from many different vantage points and experience. This is a design process not merely the exchange of information with the outcome an advance in general knowledge about the issue and each group returning to their home organization with an implementation plan. |

| Over the weekend we designed the document below except that the Insert was a description of the Invitational designShop and its theme. The Insert show below is what we used as a talking diagnostic tool for members of organizations to understand where they were in the evolution of their enterprise. Monday morning we sent our last dollars printing 6 copies and Gail headed out by car and me by foot. By early afternoon we were back at the AMC. She had sold two and me one. With the deposits we paid the rent and showed Meg our program. She said “this is a whole new ball game - what are you doing tomorrow?” “What we have to.” The next afternoon she showed up with a friend - the inventor of the smoke alarm - and asked us to explain our concept and where we were. In a half an hour, he said “all you need is more time - what are you doing tomorrow? “What we have to.” He told me to make an appointment with our bank and at 4 PM the follow day we had $75,000 based on a loan he co-signed. We had operating capital in the bank for the first time. |

| With the help of Meg and our new friend, who became a board member, we filled up the Invitational DesignShop (the outcome of which is another story) and the work which came from it kept us busy the following year and up to the Acacia acquisition. The document below - and other versions of it - became our “talking piece” well into the 90s. It content is as important today as it was in 1982. We have been through the first cycle of global transformation and are entering the second [link: a future by design - not default] cycle which will match the change of all of recorded history including he last 50 years. This is not business as usual. |

|

|

| There were three technologies that enabled us to design and produce multiple copies of this document within the time that we had. On the design side we had our own environment with over 60 feet of 7 foot height WorkWalls. We used these to create the concept of the Invitational designShop, list those who we believed would make great attendee-contributors, design the format of the document, sketch the icons and draft the words - we did a complete mock up on the walls in a matter of hours. For production we had one Apple II computer with 96k of memory, floppy disks (!) and a word processing program. This was leading edge equipment for a small organization 28 years ago. Up the road, for Monday morning printing, was a small start up company in a tiny hole-in-the-wall shop by the University that had some of the early high quality fast production yet inexpensive per copy equipment. It was called Kinkos. |

| Until this time, it was not possible to get good quality printing on colored paper fast and on demand. Gail and I designed the logic of what we wanted to say and outlined the key concepts and words. I then drew the Icons and set up the page design which was done with ink and press on letters. Meanwhile Gail wrote and edited the final document on the computer as we did multiple iterations of word-smithing. By Sunday night we were finished and were at the printer at 7 AM and on to our list of candidates. A weekend of work and one business day we had our result. Crises had turned into opportunity. We used our own method and use of (for then) cutting edge technology to execute thus demonstrating our own thesis to Meg. One phone call on her part and we had the opportunity to demonstrate the efficacy of our work and show that we were organizationally viable - our start up was on its way. |

| This was convergence. The start up energy of Boulder where you could open a business with nothing but an idea. The first emergence of affordable new knowledge worker technologies which supported a fast concept to product cycle. A community of successful entrepreneurs willing to mentor a new idea. A progressive bank which supported us all the way. Potential clients who were experiencing the first “creative-destruction” wave of a knowledge-based, technology driven, global economy. A Future By Design - Not Default - the theme of the mid-70s Redesigning the Future course - found its first business expression. |

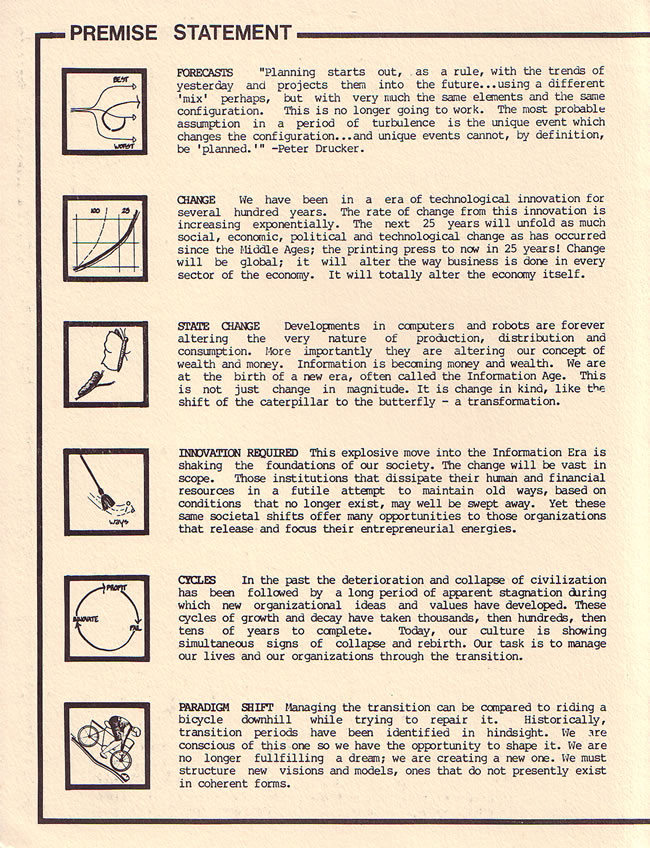

| Explaining the basic premise of our work was not easy in the 1980s. It still is not today. The document was therefore organized to challenge existing assumptions without attacking existing organizations or people. Out of this came the idea of the Transition Manager [link: transition managers creed]. The document sought to point out the new realities, indicate the existence of systemic issues greater than the then normal concerns of management and plant the seed that a new process existed which could leverage the genius of existing organizations. We wanted people to believe that they could do it themselves if they learned to work in a new way. |

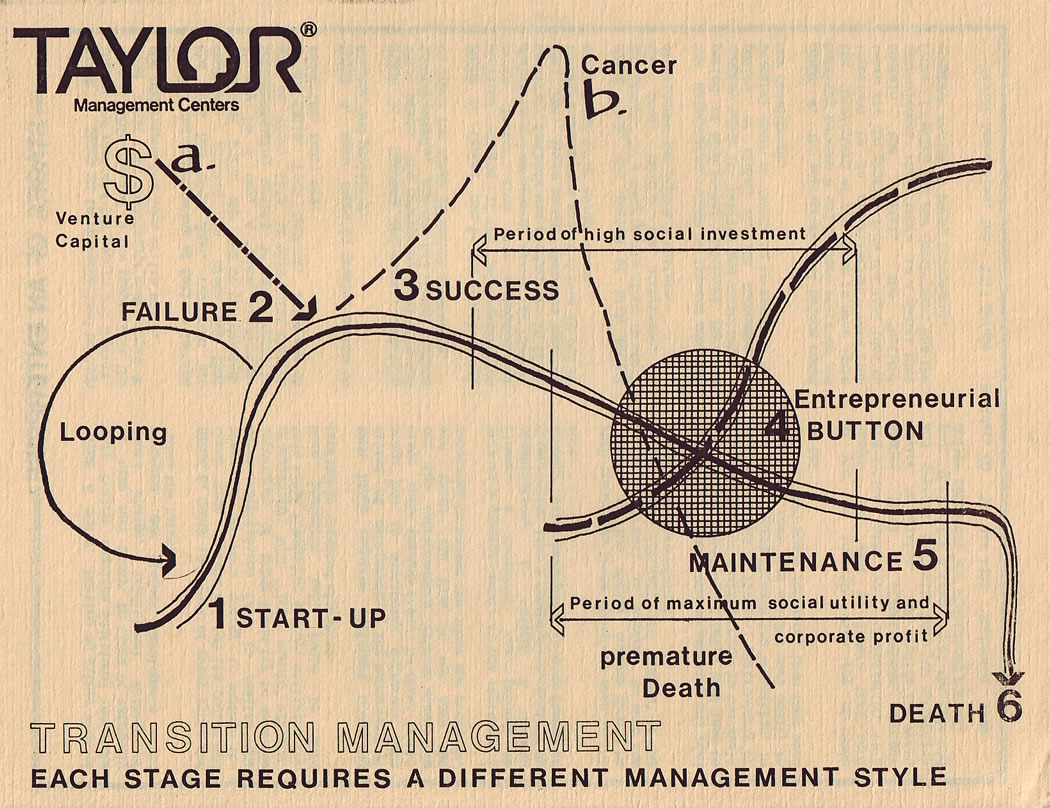

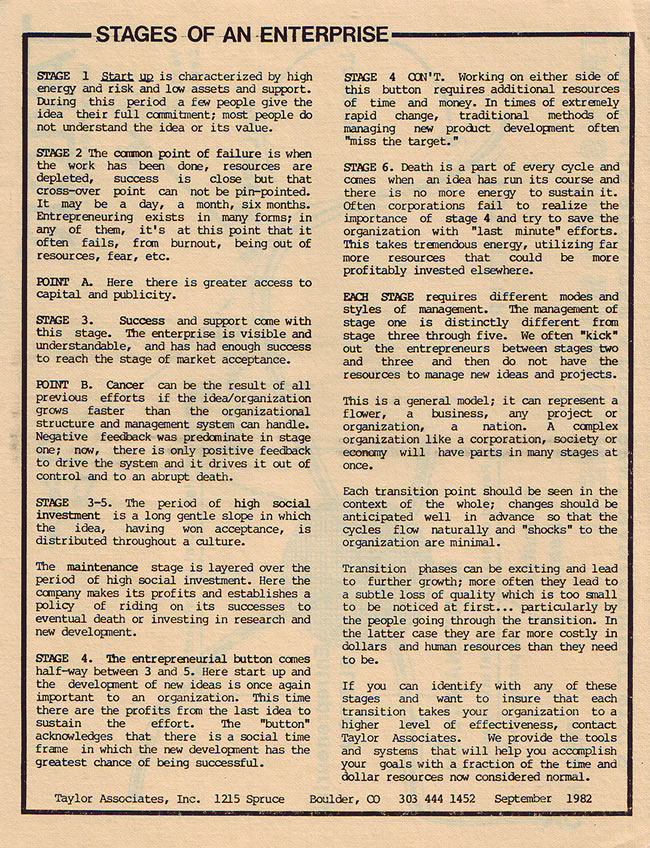

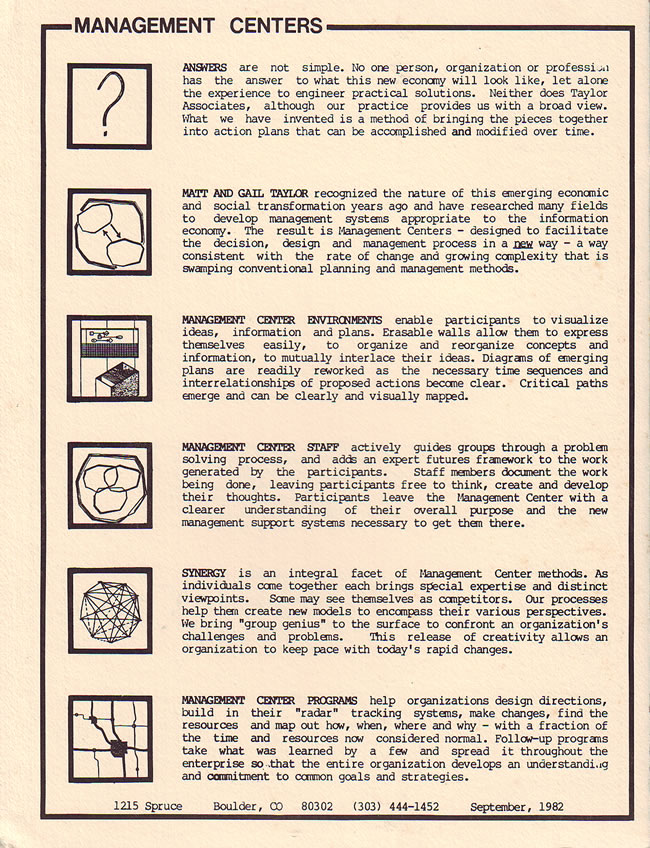

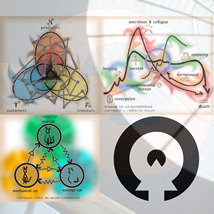

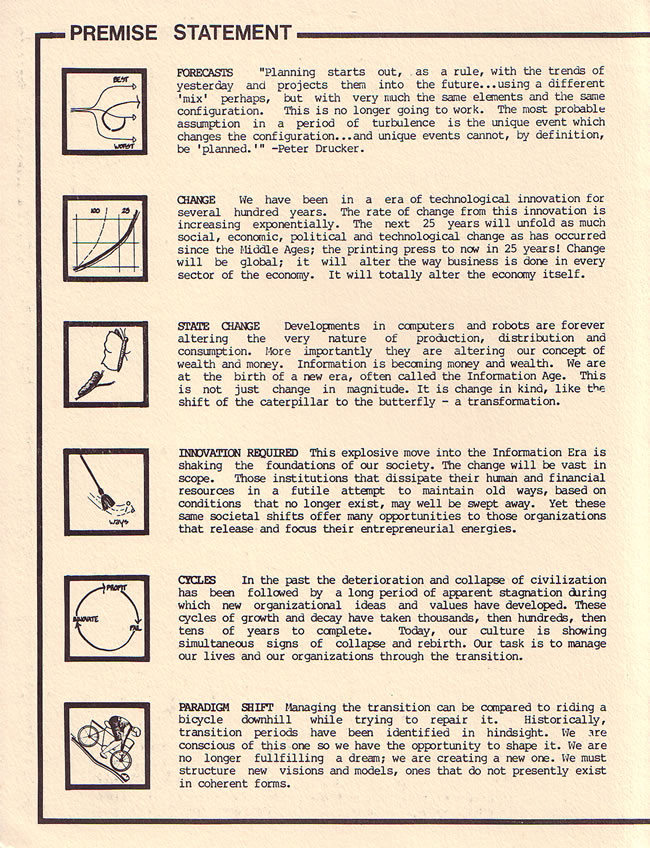

| Our printed “slide show” presented our basic argument for transformation in a series of short paragraphs each with an icon to provide a visual anchor. Where possible, the icon was one of our models or a well know social metaphor. The order of the material was logical and strategic in order to cause cognitive dissonance. The total message was emergent, challenging and optimistic. |

| The format allowed a structured yet casual conversation which could be adapted to the personality and knowledge of the client. Afterward, it served as a memory of the dialog. We sought to make the content clear yet open-ended so that it reflected our process and left room for imagination and the client to develop their own questions within its framework. When a point was made, we could move on. A resistance could be put aside and then returned to when a basic agreement and trust had been built based on other points. |

| The document claimed no authority other than the strength of its own logic. we did not want our future clients believing us - we wanted them to connect their own experience to the issues we raised and develop in their own mind the context we were presenting. |

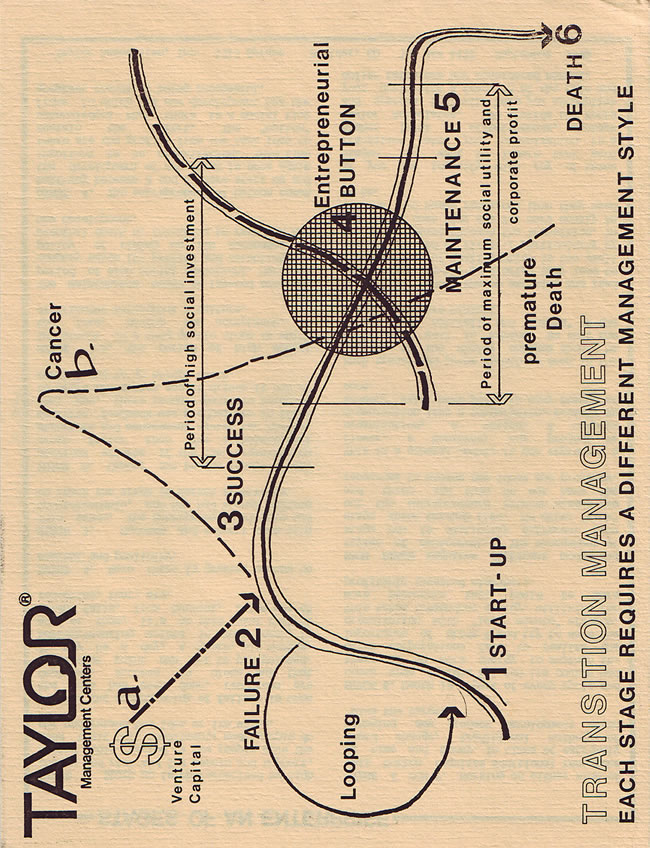

| This freed them to embrace something like an Invitational DesignShop which, in this case was the named reason for our visit, or to propose a problem of their own which we could then respond to. The Insert, no mater if it was about an event, model or circumstance brought a reason for and focus to the conversation yet it never dominated it preventing the dialog from going to where it needed to. Of course, over time, multiple inserts became available like the example of the Stages of An Enterprise Model below. |

| Another objective of this piece was to describe complex things in plain talk. The goal was not to be too sophisticated yet not dumb down the issues we were addressing. We introduced some new words (for the time) such as synergy yet only when there was no other way to name the concept. |

| The radical (i,e. to the root) idea in the document was under CHANGE. “The next 25 years will unfold as much social, economic, political, technological change as has occurred since the middle ages; the printing press to now in 25 years! Change will be global; It will alter the way business is done in every sector of the economy. It will totally alter the economy itself.” This was the premise of my 1970s work upon which MG Taylor has been built. We took a great deal of heat for it in the 70s and 80s. People could not imagine that so much change was possible and were blind to the the fact that they were already adapting to it. This document was written on the only pc on the market at the time - an Apple II. The FAX was not broadly used. A quarter of a century later, it is now published on an Internet site - where thousands come from all over the world - this documents the application of practical futurism and work method with few peers with a matching design, build, use record. |

|

|

| |

|

FRONT |

|

One of the most amusing stories of our start up years in Boulder concerned the name of our Center. I wanted it to reflect the core of our work so after some debate we settled on:

THE ANTICIPATORY MANAGEMENT CENTER

This, I thought, reflected our premise very well. It also picked up on Bucky Fuller’s idea of anticipatory design. The core epistemology of the DesignShop is design (thus its name) and our Future By Design, Not Default premise echoed his sentiment. The word management come from manus which means hand. I liked to think of anticipatory management as “the hand before the throw.” The delusions of youth - I was only 44 at the time.

We were located on the first floor of the building at the end of a long nicely designed hall with a domed ceiling. The architect’s office was on the second floor and and the stairway to his suite was adjacent to our entrance. Our front wall was a single sheet of floor to ceiling glass trimmed out in a stained oak as was all of the windows and doors of the building. Our entry door was to the right at a 90 degree angle and opened into our Library area. The glass wall facing the hall looked into our Conference Room which had WorkWalls and a 7 foot round table. I liked to work there as I could spread out my work and look down the hall and out the front glass door of the building - a nice view with a good 75 foot perspective.

The only thing on our wall of glass which was about 18 foot long were discreet white letters spelling our name in white letters . I thought it was very professional and understated and that it said it all.

One day a gentleman, well dressed and clearly successful and clearly a client of the architect came down the hallway passed our window and started up the stairs. I was working in the Conference Room and watched him go by. He went up a few steps, turned around, came back down and stared intently at the lettering on our window. I began to think that perhaps he had heard of us and was actually coming to see us. Instead, he shook his head in a puzzled sort of way and resolutely headed back up the stairs.

In about an hour the gentleman returned, and started down the hall toward the front door. After about 15 steps, he turned around rushed back, came in our front door around the corner and burst into the Conference Room where I was sitting. He was clearly agitated. “What,” he bellowed. “is an anticipatory management center?”

I asked him what he thought the word “Anticipate” meant and he said “to look ahead, to prepare for probable occurrences.” I was impressed and then asked the meaning of “Management” to him. He said “to control and organize resources and the sequence of work.” This man had been to school and was sharp as a tack - we were on a roll. So I asked him his thoughts about “Center.” “ A place” he said, “a prime resource, a point of focus.” In triumph, I said “well, now you know what an Anticipatory Management Center is.” There was a long and I thought rather stunned pause, “Oh” he said and then slowly walked out the door without saying another word. I was too stunned to stop him. He walked about 30 or 40 feet down the hall, stopped, turned, looked back, stared for a bit, slowly shook his head and then strode out like none of it had ever happened. I never saw him again.

I have thought bout this conversation many times over the last quarter of a century.

We had many debates about the name of our Center yet we kept this one to the end of our time in Boulder. It was, I came to believe, a useful ice breaker. I have always been shy and a bit of a wall flower. I hate parties and have never mastered small talk. The “what do you do” question is one that I always dread and do everything possible to avoid. How do you answer it? In the early years, “Anticipatory Management Center” never failed to facilitate a conversation and not all of them were bad. We did end up putting Taylor Management Centers on our business cards and stationery - it was simpler yet I never liked it as much. I have been trying to get “Taylor” out of the corporate name ever since - I think I will achieve this in 2008.

What you name something and how you describe it has consequences. These are not always what you anticipate. Brands that are descriptive are considered weak and vulnerable to loss. When they persist, however, they can become extraordinarily strong. I have always had the bias to name things for what they do. DesignShop for example. Sometimes it works and sometime not. I came up with the term Design Shop on June 20, 1975. It was to be a retail store for knowledge workers. The knOwhere Stores 1996 - 2002 were a partial application of this idea. The term was applied instead, in the Boulder time, to our collaborative process events and has world wide recognition today. Unfortunately, it is used so much for work which is not our process - or fails as an exemplary example of it - that it runs the risk of becoming diluted. Brand management of an idea is really no different than the “management” of a scientific paradigm or an academic concept. The Foresight Institute’s [future link] early struggle to keep the definition of nanotechnology pure is an example of this. Words matter. Words are concepts. Concepts are social models. In aggregate, they form a social paradigm within which logic and facts are exercised.

This is why we have long said that the Taylor System and Method is an OS for intelligent beings be they people teams, social groups, society, machines - all in any combinations.

In Boulder, in the early 80s, we were trying to figure out how to say things to people that they were not yet ready to hear - in fact , a message that few are willing to hear today. We had a mission [link: taylor mission] and we are still building that mission today. This mission did and still does have two parts. One is to facilitate global transformation and the other is to be a for profit corporation as a consequence of succeeding with the first. Our focus in the 80s was to change the nature of work primarily in the corporate workplace. We have always believed that the ideal and practical were one and that long range and short term thinking and planning were dependent on one another and a single exercise. Corporations and governments in the 80s were just beginning to feel the bow wave of what has been a sweeping global change. This document was not trying to get them to take their eye off the ball that represented their immediate circumstances and concerns. Far from it. We were wanting them to put these challenges into a new context, adapt a new and more powerful way of working thereby solving their immediate problems in a way that better prepared them for the times ahead - and, in a way that diminished unintended consequence not multiply them. I didn’d want the man to keep walking out the door shaking his head. Nor was I the bit interested in taking peoples money for feel-good snake oil that in reality solved nothing of importance.

Once people were in the design process there was no problem. The question was how to get them in the door for the right reasons ready to create and solve the right problems. To do this, we had to challenge long held hidden design assumptions that few knew they had. We had to do this without causing too much confusion, trauma and anger in the process. Again, in the DesignShop process itself this was never a serious problem. Outside of our environment and work flow it was and in many respects still is even after many years and nearly 2,500 successful events.

The Premise Statement was designed to exposes and bring to awareness these hidden assumptions yet do so in a way that both problem and solution were grasped together. The back of the document introduced the concept of Management Centers as a place where “systematic discovery of new options” was the routine not the exception. The management Center was offered as an invention, as a technology and method designed to release the full power of an organization. The Insert piece was always topical and intended to be of specific interest to whomever we were addressing at the time. This could be general as the Model shown on the left, it could be around a specific event such as the Productivity DesignShop - the topic of our first use of this document - or, it could address a concrete business, cultural situation such as when we worked with the Independent Bankers Association on deregulation.

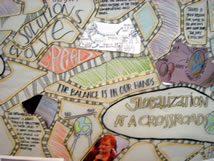

In the first version of this document, I created the hand drawn icons. In the later one shown here Cindy Cox, one of our KnowledgeWorkers, redid them based on my style yet adding her personal touch. In these days, almost all of the graphics used in DesignShop documentation were hand drawn. We wanted the look of the marketing piece to reflect the look of the final product. This hand drawn technique was predominate up to the mid 90s when electronic graphics and web posting started to take over. It is important to review this older work. While somewhat quaint, it still has a power and touch that is not easy to get in the more finished looking products of today. Personally, I still do a great deal of hand work and publish it on the web. I think that a balance between all of the graphical options is the best course to take and something that the ValueWeb should revisit. Our wall graphics continue this tradition to this day.

This wall collage was created by Alisa Bramlett in the WorkSpace at the 2007 WEF Annual Meeting. It is mixed media and became, over the week, a 30 foot long by 7 foot high documentation of all of the events which took place. This is an example of hand work to wall to photo to computer to printer to print and web to wall - a technique we have been developing from the beginning of our work. Our premise that “all media is multimedia” is a foundation of our approach to graphics.

By employing this integrated and iterative approach from marketing to event documentation on to re-use of the materials, a graphical language is created that “chunks” content and meaning. This facilitates both cognitive effectiveness and strong memory among the members of a working Valueweb.

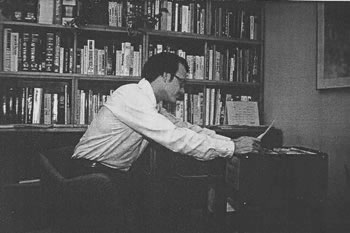

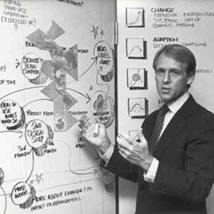

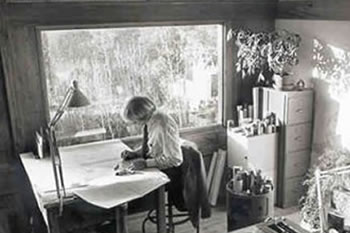

This is picture of me, taken in 1986, while working with a client. You can see the icons on the right juxtaposed with a Fuller Air-Ocean map on the left. The subject here was the interaction of global trends and their impacts - futurism then, daily business today.

This approach, when done well, integrates the marketing and sales process with the resulting work. It all becomes one seamless experience. The work actually begins with the brochure and the web site. There exists a sweet spot - a convergence of all elements for all members of the ValueWeb. This is a design goal worth remembering, pursuing and achieving.

Today, we have a greatly enhanced multimedia tool kit. This can sometimes overwhelm the content of a message and its fitness with a specific time, circumstance and place. Our message may have relevance over decades. It is necessary, however, to continually restate it so that it speaks with power in the specific moment which is always unique. |

|

|

INSIDE LEFT |

|

INSIDE RIGHT |

|

INSERT FACE |

|

INSERT BACK |

|

BACK |

|

| |

|

| There are few experiences like starting up a new enterprise. In our case we were tasked with creating a new technology and method, forging a market for it, and learning how to communicate with this market and serve it. In three years we created the DesignShop method, built three environments - the precursor of today’s navCenters - learned the basic economics of our business, and were drawing clients from all sectors of the economy, from all over the United States. The basic dna of everything we are doing today - and many things we have yet to do - were established in this period. |

| From the beginning, we conceived MG Taylor to be a ValueWeb® although we did not have the model for it until 1985 and the method defined until many more years later in the mid 90s. We never saw our clients and customers as “targets” to manipulate and sell. Nor do we take the converse role often prevalent in professional services - we do not see ourselves subordinate to those we worked for nor those who worked for us as subordinates. We saw all these relationships as peer-to-peer - a network working together to solve problems and create mutual value. In economic terms it was not about making money for us - the intent is the creation of sustainable wealth, equably shared and employed. |

| We have always worked hard to provide our clients and customers with what they ask for and seek to purchase. Yet, this alone is not enough. We act to raise both their and our awareness of what is possible and stretch all of us to achieve it - and to do so together. If we just do what is asked, we have failed. To accomplish only what is known to be necessary, at the beginning of the work, means none of us got smarter - nor did we grow our capacity nor the capacity of those who hired us and those who worked with us. In today’s world of increasing change and complexity, this is to lose ground. It certainly is to abandon art. There is a whole new society to be invented and this cannot be done in the abstract. Each opportunity to improve a condition of today has within it a future possibility to be found and developed. The past present and future are tightly linked. The future is won - or abandoned - one project at a time. |

|

|

| From the beginning, our work was based on the assumption that sweeping global change was becoming the driving force of an unprecedented human transformation taking place in a timeframe far more compressed than any prior period. That this could not be dealt with by merely getting better with the agenda and methods of the status quo. That a personal, organizational and global social transformation is required to meet the challenges which we, as a species - who increasingly generate the factors of our own evolution - have created for ourselves. That even the many wondrous opportunities before us present equally profound downside potential if they are not understood and approached systemically. That no individual, organization, government or country - not matter how accomplished or rich - can understand and respond properly, alone. |

| We believed - and still do - that a new way of thinking, of working and organizing is necessary for broad success. This view of the future and Humanities’ potential defined our approach to business. It determined how every project was approached. It defined success criteria. It required GroupGenius® processes to establish GroupGenius. Given this, how our work is communicated has a direct effect on how it is executed. |

| How our work or a product is represented and sold is much more critical than just getting the job. Sold wrong - or the implementation process conducted poorly - can engender a disaster not just a marginal business outcome. The level of trust and collaboration among all those involved must be very high. This is a necessity - not to protect reputation and thus get more work - it is necessary for accomplishing the work at all. We found that the culturally accepted rules-of-engagement and ethical standards of business were not up to the task. We learned that times change and how the communication-marketing-contracting process works in one era does not translate to another. Principles do translate from one circumstance and era to another. This period in Boulder was a time when we reached congruency between message, work opportunity and results. For this it is worth reviewing today. |

|

|

| |

|

Photos From the Boulder Era |

| |

| A DesignShop participant uses the library to do research. Besides books and magazines, we complied relevant documents before each event. We also had electronic data bases and on-line connectivity via an early precursor of the Internet. This space also had a couch and chairs as it served as our Entry. |

|

|

| Architect Art Everett of Everett, Zeigel Tumpes and Hand Associates, designers of the Boulder Mall, whose offices were above the AMC, working on an Affordable Housing concept at the first DesignShop held in our new space. This was a variantion on one of the four designs we did for the project. |

|

|

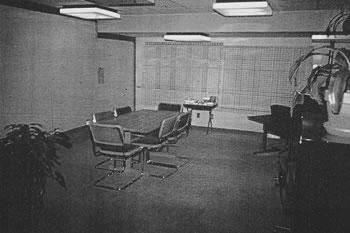

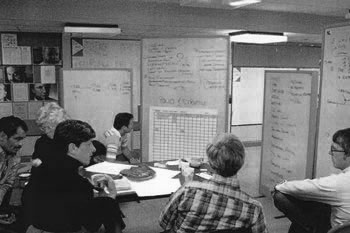

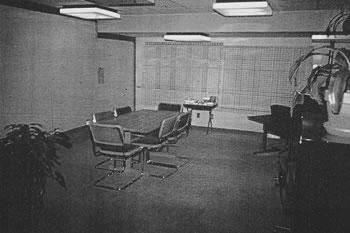

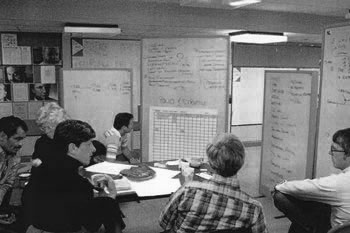

| A team working in the Conference Room of the Boulder Anticipatory Management Center. This picture shows the glass wall which looked out into the building’s Entry Hall. Our first semi-custom WorkWalls and round tables were built for the AMC. This room was my favorite place to work during the Boulder years. |

|

|

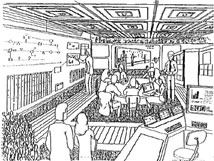

| The US Army Corps of Engineers working on recreating the Captain’s training program which became a model for the entire Army. Four days after this 5 day DesignShop, the new process was approved by the Chief of Staff and in operation within 9 months - usually a three year process. |

|

|

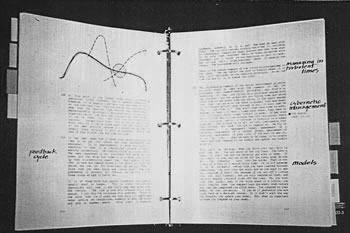

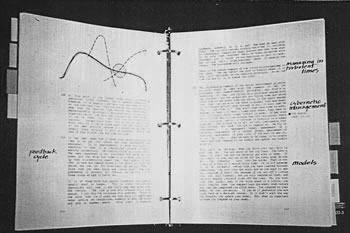

| The Productivity DesignShop Documentation. This was the first Invitational DesignShop and it brought 8 organizations together to look at the productivity issue which was a hot subject at the time. Our approach, however, was to bring strategic and systemic issues to the exercise as a context for this subject. |

|

|

| This was our Project Management room where AndMaps™ and Time and Task Maps were built with client teams. This space was used for break out areas during DesignShops and a client project room between events. The walls allowed our clients to experience “Working Big,” many for the first time. |

|

|

| OPM participants in a group dialog after reporting out teams during the SCAN portion of their DesignShop. When we first opened the AMC we were able to facilitate groups between 25 and 50 in number. Over time, we created the capacity to serve 75 - the number of our last DesignShop in the space. |

|

|

| Jim Toohey, architect, worked at the AMC and, after our acquisition, designed under contract, several Acacia environments as Acacia did not acquire the design, fabrication part of the Taylor organization. Here Jim is drawing a strategy map during the Independent Bankers Association DesignShop. |

|

|

The Office of Personnel Management members working on their implementation plan. in addition to long 20 feet fixed WorkWalls, we had many small ones which stood free and moved around easily. A early version of our rolling walls, they provided screening and allowed content to be easily moved between teams for iterative work.

|

|

|

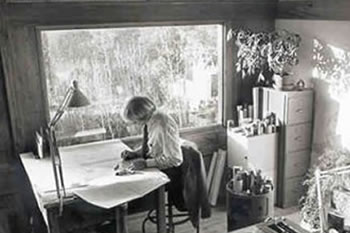

| When not at the AMC we worked in a detached studio by our house on 3 acres bordering a national forest. The house and studio, heated by solar and a wood stove, were at 8,000 plus feet, a few miles away from a glacier which supplied water to Boulder. Looking out the windows there was nothing but trees. |

|

Related Links:

click on graphics to connect

|

|

The MG Taylor Mission evolved out the Redesigning the Future Coarse and he renascence project of the 1970s. This version of it was refined at the end of 1982 and published with our 1983 Stockholders report.

Although the language shows its era, we have not changed it since. There has been no need to. This article provides commentary and relevant links. |

|

|

| Abscapes™ is a term which I coined in the 80s while exploring a new graphic art form. I am still exploring it and still intent on producing some major works based on this approach. One has been commissioned yet so far the muses have not struck me with lightning nor has business afforded the time necessary for its conception. The idea of Abscapes is primary to our concept of multimedia and thus the material in this article. |

|

|

| A reflection on Boulder written 20 years after we first arrived there and launched our enterprise. Boulder was perhaps the best place possible for us to do our start up. It could not, however, provide enough work and resource for us to grow it to the scale necessary. I have fond memories of the years there. |

|

|

| One of the Taylor Axioms is “you can’t get THERE from HERE - but you can get HERE from THERE.” This page documents our 1982 THERE in regards the integration of technology with the environment and work processes. This get to the heart of what we mean when we say a new way of working is required. |

|

|

| We proposed four architectural solutions for the Boulder Affordable Housing project - three of our designs and one of architect Glenn Small - none of these were chosen for the final design The project was built years after we had moved to washington DC. Our main task was to solve the problem and this entailed developing a public-private corporation which was the key to getting something done. Our most comprehensive design encompassed many elements which have recently become icons of the green building revolution - again showing the two generation cycle process. |

|

|

| A Future By Design Not default has been the driving force behind MG Taylor since the mid 70s when I developed this thesis. It became the theme of the 06 Davos WorkSpace. This paper - in five parts is my most recent statement on the subject and a history of its path from a 1974-75 Seminar to the World Economic Forum. An extension of this thinking-in-action process is Worthy Problems which we promoted as the 08 AM them. |

|

|

| The idea of Worthy Problems and Worthy Projects as a systematic program came to me after the Boulder years. A number of the Worth projects, however came from the Renascence project experience. It was these projects and the Renascence experience that alerted me to the necessity of creating a Method capable of facilitation great change and complexity. This was the direct originator of the work done in Boulder. |

|

|

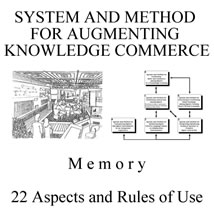

| This summary, in four sections, of the memory aspect of the Taylor Method defines Strong Memory as a key element of the system and method. The full development of Strong Memory took until this Century yet you will find aspects of this approach in our work, and description of it, during the Boulder years. The marketing piece illustrated here and the act of documenting it on the www, itself, is an application of the method. |

|

|

| iteration6 is a critical paper to read in order to understand the development phase that presently occupies us. We are in the later stages of this period and are already overlapping with the iteration7 period. The iteration6 paper defines the even conceptual phases of our work from concept to ubiquity of application. It also tells how we got to Boulder in the first place which sets an amusing context for this document and its story. |

|

|

| This final link documents 20 years of Taylor environments, 1985 - 2005. These works are all the direct decedents of the design work done 1980 to 85. Bill Blackburn, a client and Board member at that time, still works with us as an active designer on the AI and tsmArchitecture design teams. Jim Toohey, designed much of the built projects between 1982 and 1985 - the last, the Orlando Center is the oldest work featured in this tour. A quarter century of work, which has challenged the foundation of the conventional workplace, emanated out of the early Boulder years. |

|

|