|

Building a Masterpiece: The Sydney Opera House

click on icon to order book |

|

|

|

|

| |

In the years that followed I was often asked questions about the Opera House, questions that kept the building very much alive for me and my family. No other work I have been involved in since my work with the Opera House has so changed my life.

My renewed contact with Sydney and my work with the refurbishment of the Opera House-- brought about by the by the Sydney Opera House Trust and the Government of NDW under the administration of then premier, Bob Carr--has felt like a wonderful welcome back to Australia, a hand extended in the spirit of reconciliation, a hand I shake with warmth and gratitude.

Jorn Utzon

2006 |

|

|

a Story of Innovation Reconciliation and Love |

| The story of the Sydney Opera house is one that started as a fairy tale, had a tragic middle and is emerging as a tale of reconciliation and love of art and creative work. |

| Aspects of this story are all to common. The end is not. Rarely do politics give way to decency and common sense. Rarely does an idea so capture people that they stay with it for generations. Rarely does the rejected creator of a work get invited to return to the effort. This, then, is a mythical story which has much relevance for our world today. |

|

|

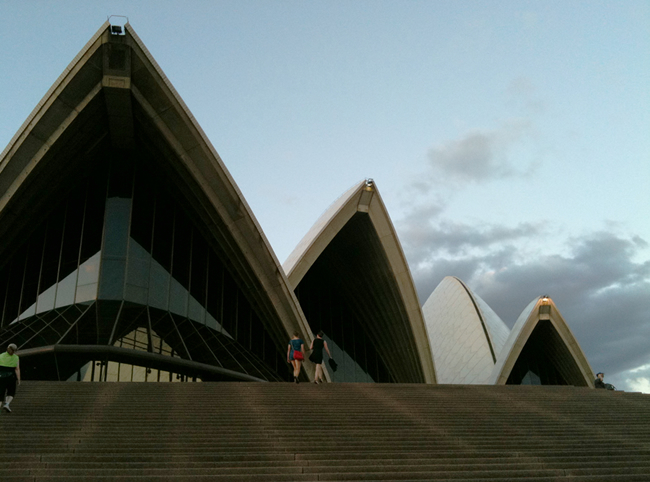

| I was only generally aware of the Opera House story and had never seen the work until I came to Sydney in March of 2010 to facilitate a DesignShop® event on the future viability and sustainability of Australia. |

| The Opera House, one of the great works of the 20th Century and of all time, became for me the icon of my trip. It, as a work of art, and as an experience of building, exemplifies a major social attitude - investment in the COMMONS - we have to relearn if we are to successfully recreate our world. |

|

|

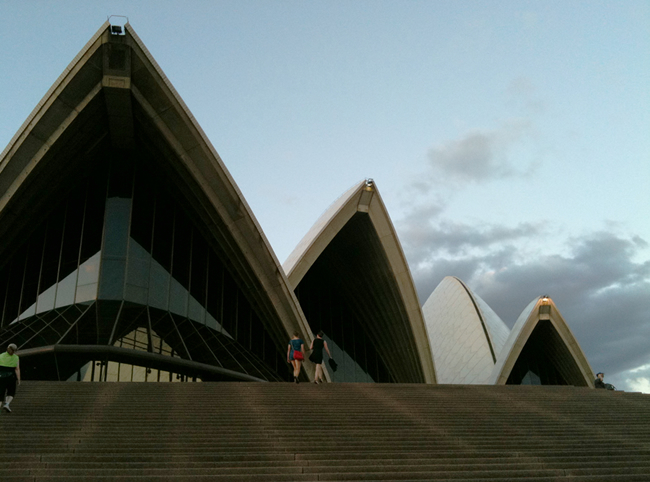

some views of a masterpiece |

|

| The setting of the Opera House is spectacular. It is on a point of the harbor with the land warping around it so that the building is viewed - and can view land and sea in return - from a variety of perspectives in a landscape which varies greatly in architecture, nature and use. |

| Prior to the Opera House being built the site was used as the Bennelong Point Tram Depot. This kind of use of a site like this was typical, throughout the industrial world, in the 30s, 40s and 50s. In my youth, where the land met the ocean was commonly refereed to as “wastelands.” A viewpoint which caused a great deal of ecological damage. |

| Today this part of the Sydney Harbor is a recreational area, a mixed use area of offices, retail, hotels, apartments and a transportation hub where ferries, trains, buses and walking malls meet, creating a lively urban setting. |

| The Opera House is a destination, an anchor and an Icon of this place both expresing it and creating it. |

|

|

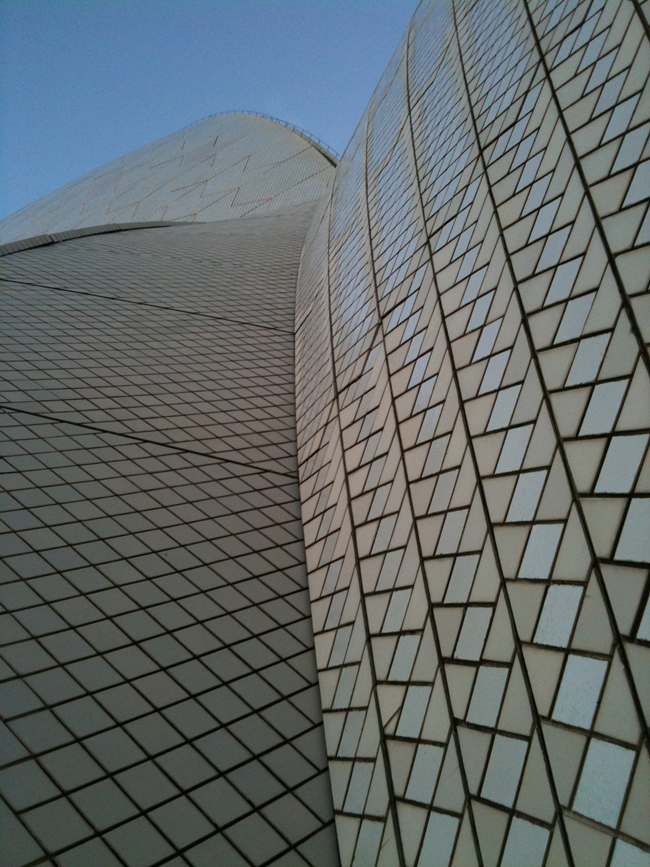

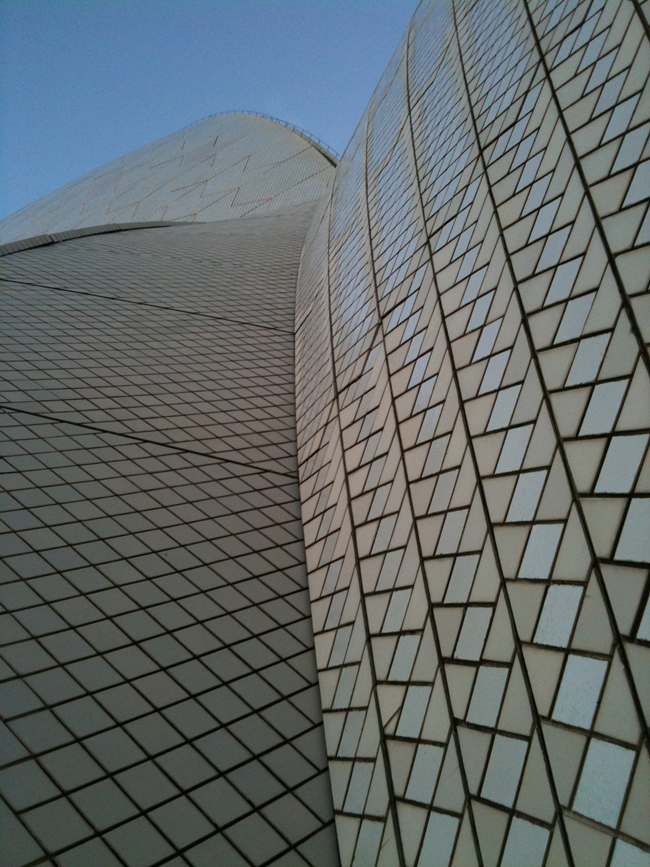

| This visit, I was on site only a few hours. Enough time to walk the exterior and enjoy dinning in the Opera House’s excellent restaurant which makes every aspect of the experience a work of art. During this period, as the progression of the pictures show, time went from early evening to night. The pictures were taken with my iPhone camera. What can be seen is that the Opera House responds to the changing light in a life-like way. |

| The roof tiles were developed for the building. They are perfect for their task. Made of two colors and shaped to refract and reflect the light in a way that makes the great “sails” a constantly changing experience, at one moment almost translucent and ethereal, the next transforming to solid carved rock. |

|

|

|

|

| There are few human structures which deliver the intellectual and visceral impact as does this master work. I am told, and from the pictures I agree, that the interior spaces - which were not executed according to the architect’s detailed design - do not have the life and impact of the exterior. Perhaps, as the building is renewed over time this fault will be removed and the idea of the building restored. There are signs that this will happen as Jorn Utzon was reengaged, after three decades, in 1999 to create a document of Design Principles to guide the work of future generations of architects as they work to conserve the building and perform necessary modifications over the expected centuries of life. This wise and gracious act healed one of the most grievous and unfortunate breeches in all of modern architecture. |

|

|

| The concrete was pre cast, in pre stressed sections, some spanning over 160 feet, erected with cranes of unprecedented size for the time without continuous scaffolding. Great care was taken to make the castings come out of the plywood forms “finished.” |

| It took several years and many iterations to design the shell shaped roof members and accommodate their extreme cantilevers. Computers, just ten years old at the time the project started, were used to calculate the stress as were complex models. Common practice today, almost unprecedented then. Engineers had to write the programs they used to do the engineering. One young engineer went on to work with Doug Engalbart at Xerox Park. |

| The collaborative process between architects, engineers and contractors was highly interactive, mutually supporting and creative without the usual clashes so common even to this day. It can be said that many of the modern techniques necessary for building large contemporary structures were invented and developed on this site. Many of the young engineers and builders established distinguished careers in the years which followed the completion of the building. A whole generation of workers came to build and stayed becoming Australian citizens. Suppliers throughout the world created new products many still on the market today. |

| In the 1960s, if you wanted to learn how to design-build, this was the place to be. This project was architectural R&D at its best and a tribute to the leadership of Australia who saw it though to completion and steward the Opera House to this day. |

|

|

|

|

| Few works of architecture have the ability of the Opera House to project such a strong sense of shelter outward to embrace the terraces surrounding it while bringing this monumental platform inside. You have it right when it becomes impossible to imaging the site without the building or think of the building somewhere else. |

| The Terrace which surrounds the Opera House is the roof over the 1,000 rooms which make up the infrastructure of this complex of opera, theatre and music halls with all the attendant functions of an arts center. These distinct facilities are visible by the shell like roof structures. The complex of several buildings - all connected under the Terrace - divides the platforms into a number of smaller spaces creating an unusually successful outdoor social space which is often used for events. During my visit, there were patrons going into one of the theaters for an evening while many people were strolling around the building, sitting on the steps, and generally treating it like it was their own back yard. This was all done with a casualness and familiarity that reminds me of the Mall in Washington D.C. People are comfortable with this work and “own” it without pretension. For all the impressiveness of this structure it does not feel monumental - it feels like home. Over the 50 plus years of it’s existence, the Opera House and the people of Sydney have formed an enduring relationship. Great architecture is created and sustained only by integrating the process of Design/Build and Use. Ownership is usually the critical missing ingredient in the making and keeping of great architectural art. |

|

|

| Work was nine years underway when a change in political regime caused the withdrawal of Utzon from the project. The issue was that the new Minister for Public Works sought to remove the architect from control of his work in a way that would have been unprecedented in Europe but was not, apparently, in Australia at the time. A controversy erupted over this that still echoes to this day. |

| By this time most of the structural and construction issues had been worked out. The real victim was the interior design which Utzon intended to be fabricated out of great sheets of plywood by a technique pioneered by a Sydney entrepreneur and manufacturer, Ralph Syminds. The design solution addressed the acoustic issues inherent in the shape of the spaces and also would have achieved an interesting, organic counter point to the structure. |

| With the assignment of a new architect, the interiors became much more traditional in their rendering and are regarded today as the major flaw of the building - a condition that hopefully someday will be remedied. |

|

|

|

|

| In this period, I was working to integrate the design-build process and had become well aware that the prevailing attitude of “ownership” was that any arbitrary decision on their part was ethical, legal and necessary. The architect was but a hired hand and subordinate to whatever demands were placed on him often including the contractor who was considered to be the practical expert. My frustrations with this situation lead me to explore the tight integration between design, building and using. This lead to the work I am doing to this day. |

| Fortunately in the case of the Sydney opera House - despite the removal of the architect - the new architect, with the engineers and builders, maintained the collaborative way of working which had been in place since the beginning of the project. If this had not been accomplished, the entire work might have been compromised beyond repair. The work proceeded well post Utzon yet without his special genius. Despite everything, the passion to create a great work prevailed. The result is not without it’s flaws yet it must be said they are only seen when held against the highest possible standard. This work is a remarkable achievement and a tribute to everyone who worked to breathe life into it. |

| Works like this do not happen by accident. Incompetence will never achieve them nor will carelessness. Work like this comes into being only by the love of the work as an end in itself. Only by passion and the application of genius will this kind of work come to be. Only by GroupGenius. |

|

|

| Two icons converse across a placid bay. This is one aspect of Armature as conceived by architect Herb Greene. The interactive citizen involvement and art is still not here. This second aspect of the Armature concept is possible in this environment. |

| A “signature,” iconic work creates brand for a city or region - in this case for the entire continent of Australia. It stands for an idea and an attitude. It captures and expresses the meaning of a time and place. In terms of “art as a concrete expression of abstract values and long range goals-aspirations,” it is a clear rendering of social scale art. To illustrate, if Sydney woke up one morning and the Opera House was suddenly gone, what would be the reaction? What loss would be felt? What sense of identity gone? What would the rest of the world feel? |

|

|

|

|

| A building at night is always at it’s best. The essence of what it is is free to be seen uncluttered by too much detail. Personally, I always seek to develop a design with this standard in mind so that it appears in the daylight as “clean” as at night. This is a tough standard yet a worthy goal. It brings the built result much closer to the mind-space vision of it. |

| The joy of practicing the architectural art is that the concept has to travel through a series of iterations to become a practical result. When this can be accomplished without doing violence to art, engineering, manufacturing, construction, economics or use, then an integration rare in our social experience has been achieved. A process has been demonstrated that is a necessary ingredient in a time such as ours. |

| This view of the Opera House at night reveals the structure which makes the magic possible. This structure was made possible by a carefully engineered process that was an artful mix of science, technology and innovation. The integrity was not to give up the dream because of the demands and difficulty of making the dream real. The integrity was to stay with it until the answers could be wrested from Nature in service to Nature. The integrity was not to settle for anything less than the very best the team had to give. In a society too often over focused on taking, this work is an example of giving. In doing this, a few hundred people - from architects, engineers, contractors, crafts-persons, tax payers, patrons, administrators and political leaders made a great gift to the commonwealth of the world. |

|

|

| The press of my work over the last two months has been a string of 20 hour days until now as I finish this writing. My visit to the Opera House has been my sole vacation - time off free of any concern other than just being a consumer of this exhilarating and demanding goddess we call architecture. I walked back to my hotel that night renewed. On the flight back to the U.S., reading Building a Masterpiece: the Sydney Opera House - a kind and generous gift from my Australian collegues - was a peacefull affrimation that projects like Xanadu will some day achieve that critcal transformation from sketch to built reality. |

| Much of what we can know about civilizations and times long gone is by the art and architecture they produced and left to us. Our experience of these works gives us the essence - the mundane and negative aspects of their lives having been swept away - of what people of these times had to say about their time and contribute to ours. Art, according to Rand, eliminates the irrelevant. Architecture, according to Wright, turns each moment into an act of living art. Great art expresses what is important and reminds us to remember our aspirations and dreams and not give them up. |

| If ever there was a time when Humanity has to remember our best aspirations and see beyond the petty conflicts and confusions of our present circumstance, it is now. How important is this work of art which is a temple of art resting on this point in a beautiful bay? I say important beyond comprehension. |

|

|

|

| Civic architecture is distinct from other kinds. What type of building can become a “civic” piece can vary widely. It can be a monumental work or relatively small. Private or publicly financed. A residence, school, office building, apartment building, church, tomb, factory, government house, hotel, recreational complex. All of these at some time and place have risen to the status of being a strong civic expression. What makes it civic is the work’s relationship to the place where it is built and used. And in how the symbol(s) it defines captures the sense of the population and expresses it in a public way. How a work becomes iconic is another matter - this is a consequence of “chunking” which is an illustration of mind-like functioning. If a work becomes a Global Heritage Site is even more rare. The Opera House is the youngest building to achieve this distinction. I do not believe that this status can be achieved by fiat and deliberate attempt. It happens when a certain kind of magic happens. It happens when a rare combination of circumstances combine. It is a result, not a cause. These circumstances can be deliberately brought together in sync with complex ones not subject to intentional human action. A successful outcome, however, has to emerge organically as an authentic consequence of a proper process. |

| That a building intended to or happens to emerge toward civic status will become highly controversial is almost axiomatic in today’s societies. When this ceases to be it will certainly be a very dark or enlightened time. That such a building will be highly innovative and require new technologies and methods is also almost always true. The challenge in the effort is a major factor of it’s persona and that which attracts the talent and will to make what has not been made before. |

|

|

| People sometimes question the role of art in a society beset with so many critical problems. On the contrary, I argue this is what we need to be paying attention to far more than we do. In our media-world, what is our “art” telling us about the nature of the world, humanity, and each of use as individuals? What “instructions” are being put into our minds millions of times every day? What distractions cause us to ignore which issues - putting our better futures at risk? Has art become the slave of the new media Roman Circus? Humanity has become the programmer of our own evolution. We evolve in response to the world we have made not the one we were birthed in. Earth has passed the tipping point of becoming a human artifact. In a generation this process will be complete. Will this be a sterile dead place being consumed by mindless consumption? Will it be a human-gaian work of art - a garden for all life? What is our vision of the Human Enterprise? Will we fiddle while Earth burns? |

| Who will have written the Human Opera? our worst fears and bad habits? Our traumas from so many failed civilizations? Or, our best image of ourselves? Our greatest aspiration? Our most joyous effort as the expression of our love for each other, all life and the living of life? These are no longer abstract questions. It is in our power not just to ask them but to answer them in action - in fact. This is our challenge, and trial, and opportunity. That which we can imagine now we can do in the next generation. The doing will be the sum of millions of projects and billions of acts. It cannot be controlled - it will emerge. Our design-build-use process can be designed, learned and practiced. May we do at least as well as Jorn Utzon and his inspired band of merry builders. |

|

|

posted:

April 1, 2010 - revised April 3, 2010 @ 10:46 AM Nashville |

|

|

|

|

to: Guggemheim @ 50

|

to: Authentic Architecture |

to: Amature System |

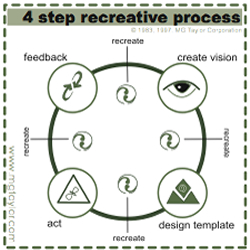

to: 4 Step ReCreation Model |

|

| GoTo: Sydney Workshops - 2010 |

|

|

|

|

| GoTo: Basic Architecture Practice |

|

|

|

|

| GoTo: Planetary Architecture |

|

|

|

|

| GoTo: UpSideDown Economics |

|

|

|

|

| GoTo: Noise - the hidden pollution |

|

|

|

|

| GoTo: American Myth - the flaw |

|

|

|

|

| GoTo: ValueWeb Architecture |

|

|

|

|

SolutionBox

voice of this document:

VISION • STRATEGY • DESIGN DEVELOPMENT

|

click on graphic for explanation of SolutionBox |

|

|

|