IDIAP Presentation

November

24, 2005 |

a 25 year action research lab:

human cognition, communication, design

part one of three

|

Note:

In November, 2005, I gave an informal talk followed by dialog and then me being given demonstrations of various works in progress at IDIAP [link: IDAP research institute].

It was both a pleasurable and enlightening visit.

I started this web article the afternoon before. My intention was to put my thoughts in this piece, supplemented with appropriate links to support material from my site and other sources, and use this to supplement my remarks. Unfortunately, at two in the morning a few hours before we were to start, I had a disk crash that left me without computer until I returned to the U.S.

I finished my notes, by hand, in my FUTURE VIEWS Notebook - see below - and used this to organize my remarks supported with pages from my web site which I tagged on their computer projector system prior to the talk.

What follows is a reconstruction and elaboration of my remarks and various topics that came up during the day.

For an outline of major points, concepts and conclusions...

GoTo: idiap presentation 05 summary

Matt Taylor

December 22, 2005

|

|

|

page FV 16 November 24, 2005 |

click on graphic for full screen view |

| I have titled this talk 25 years of Action Research in a Living Lab because this best highlights two aspects of my work which frames what I wish to say to you based on my understanding of the nature of your work. First, that I am reporting experience - not untested theory. And, this experience is made of 25 years facilitating the learning and creative processes of a wide variety of people in collaborative environments that my associates and I have designed, built, equipped and operated by a patented process of our own invention. The tool kit utilized in these environments have been made up off-the-shelf computer and multimedia technology configured by us and employed to augment human cognition based on a model I conceived in the 1960s and that MG Taylor has further developed from the early 1980s onward. To highlight further this aspect of our work, the web page title of this paper is As We May Think - a reference I am sure you are familiar with [link: vannevar bush in the atlantic monthly 1945]. |

| I choose the four graphics that make up the Masthead of this Paper because they illustrate key aspects of this experience: |

click on graphics for additional comments |

|

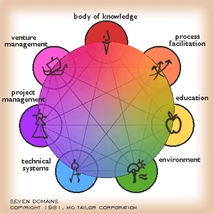

| We had to develop a number of new Models and definitions - terms of art - in order to precisely communicate what we were doing. Shown here is the 7 Domains Model which identifies the critical aspects that must be managed in a certain way in order to make the environment necessary for the creative organization. |

|

|

| The Taylor Method has been employed over 3,000 times with organizations of all kinds all over the world. It integrates the physical environment, work processes and technology in unique, “mind-like” ways to facilitate what we call “GroupGenius.” Leaders commonly report that they “got a years work done in less than a week.” |

|

|

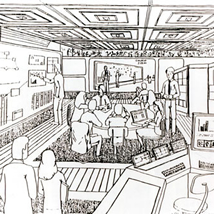

| The physical environment as “place-maker” is under rated in our society. It has to create “Strong Memory.” It must hold the energy of a diverse group of people from different cultures - all coming with different agendas. It must, in setting, shape, form and character, adapt - minute by minute - to practical user requirements. |

|

|

| This diagram of our 1982 technology vision of a NavCenter illustrates the knowledge augmentation processes of the Taylor Method. We have employed “run, walk, run” methods by using “KnowledgeWorkers” and off-the-shelf technology, progressively automating long practiced work protocols which reflect the algorithms of the Method. |

|

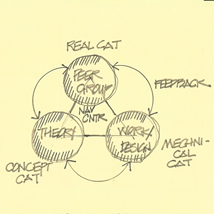

| The primary method we have employed to achieve a greater integration of technology and collaborative - creative work, is what we call the 3 Cat Process. |

|

| The 3 Cat Process is simple in concept and often challenging in practice. It requires a rigorous personal process and an even greater effort, due to embedded habits, on the levels of team, group, community and organization. |

|

| There is a strong tendency for specialized communities to “two-cat” according to the cognitive bias inherent in their work focus. Academics, for example are inclined to study the “real” cat and build a theoretical “concept” cat. They often ignore the learning inherent in the making of a “mechanical” cat. There exists in some communities a pervasive sense that not only is “hands on” work of little value it certainly is not, in any case, within the purview of an intellectual. Craft and applied arts workers usually study the “real” cat thoroughly while applying what they observe and have learned to making artifacts of various kinds. They have a habit of eschewing theory as useless and, if you can judge from the common attitude, corrosive to the act of doing real work. |

| This unfortunately common expression of the “soul/body” dichotomy has long been deeply embedded in our Western Tradition. I set out, in my teens [link: starting work 1956] , to reveal and destroy this destructive meme. It fosters a harmful fragmentation of work, excuses often the inexcusable in the realms of business and politics, and supports an organizational theory of hierarchy, levels and “stovepipes” that no longer functions well nor can remain requisite with the changes and demands of the world that humanity has made - and is now reacting to - often negatively. |

| As humans progressively acquire the means to alter physical reality, all life forms - including our own - and our own society, the “real cat” actually changes as a consequence of our direct actions. Human evolution is increasingly driven, both mentally and biologically, by our own cultural ecology which we are creating by numerous individual and “separated” acts. Soon, all three cats will be short term variable, co-dependent and mutually influencing. |

| “Two-catting” leads to stagnation because once theory and reality - or reality and design/work - seem requisite with one another there ceases to be information. Gregory Bateson [link: bateson’s epistemological work] reminds us that “information is the difference that make a difference”. “Three catting” increases the complexity, thus information factor, by a significant amount. Multidisciplinary work is essential for good design. Intellectual ghettoes are comfortable but dull. Researchers have to bridge this self-imposed information abyss and so do architects - the nature of their work demands it. This is perhaps the closest tie between us and makes a firm basis for IDIAP and MGT to bring value to one another. A real researcher has to gather experience and information, build a synthesis, add a dash of insight, propose implications and uses, and demonstrate viability. A real architect has to build philosophy that also keeps the rain out and successfully expresses the values of its users and society as a work of art [link: definition of architecture]. We call this Design, Build, Use - feedback, Iterate. Multiple iterations of work that span observation, model building and making drives error out of the result. Success in research and in architecture requires rapid cycles and tight integration of the entire creative process [link: creative process model]. Because of the vast amount of knowledge available, thus “vertical depth in every field, the complexity and rate of change of our society, the high standards required to be world class, and the competition for mind share, “products” (intellectual, service and objects) that succeed require the collaboration - not merely cooperation - of multidisciplinary teams. Complex products require emergent not deterministic research, design and production. The old ways of organizing and working do not promote this. |

| The Center triangle in the 3 Cat Model is the system integration function we call a NavCenter. A NavCenter® [future link] is the highest expression of our Method that we can build, at any given moment, based on the principles and criteria expressed in the 7 Domains Model. The NavCenter® is an environment designed to facilitate knowledge work [link: knowledge workers - drucker‘s concept] in all it aspects from individual work to that of teams and large groups. It is in these environments that we do our work. They are also our research lab wherein we observe and learn about human creativity and collaborative processes. Over the last 25 years, more than 2,500 major organizations have attended DesignShops® [future link] provided by MG Taylor or our License holders. DesignShops are typically three to four 12 hour day events for 75 to 125 people in which a challenge is explored in depth, solved and and action plans developed. In these environments, as before noted, which we have designed and built, employed a patented process of our invention, configured technology to our specifications to augment the work, we have facilitated tens of thousands of people from all walks of life, disciplines, regions of the Earth and representing a broad range of human cultures. The problems solved have covered the entire range of human endeavor [future link]. Our Method is based on iteration, recursion and feedback [link: table 2 - principles of iteration feedback and rule of recursion pdf] . This is so within the inherent structure of the work, its application in every event and activity, and in the conduct of the practice of the work as it is has evolved over time. |

| The organizational strategy that MG Taylor promotes as being best fit for the knowledge-network-creative economy is a ValueWeb® [link: valueweb architecture]. Organizations, today, cannot meet the challenges they face by utilizing only the financial and human capital that are within their own “skin” of ownership and control. The world is too complex and they will be overwhelmed by the Law if Requisite Variety [link: ashby law of requisite variety]. A valueWeb employs network strategies to accomplish flexibility, diversity, configurable on-demand expertise and resources, and critical mass. It is also, like a traditional organization, made up of formal structures and protocols providing the ability to create mission, focus and operability as a corporation does without sharing many of the limiting factors inherent in the hierarchical and bureaucratic organizational schema. There is not time to explore the valueWeb concept in depth here. What is important to our discussion is that MG Taylor has undertaken a scope of work that can never to fully explored or practically employed by one single traditionally structured organization nor even a single industry. We knew this when we started. Our work requires that we create a true ValueWeb as both an expression of our method and as the practical means of doing our work at the scale required. We are at the threshold of achieving this [link: mgt iteration6 personal reflections] by building a network of NavCenters, owned and operated by different organizations, yet connected by spirit, global mission and work method. Doing so at scale capable of solving persistent, global systemic problems is intrinsic to MG Taylor’s Mission [link: mg taylor mission statement 1983] . Why this is so requires a brief review of my background and what factors lead us to the creation this enterprise. |

| I was born, in 1938, to a second generation Air Force family, entered school during WWII and lived on Air Force bases until I was a teenager. These early experiences shape how I think of community and technology to this day. In today’s language, I grew up in mission focused, intentional communities that had global reach, were a meritocracy at heart and relied extensively on technology to accomplish their mission. Technology that did not work properly or was not employed properly jeopardized the mission and could kill you [link: queens die proudly 1947]. In this world my friends were young pilots and I played in airplanes when they were in for Maintenance. My first flight in an airplane was the co-pilot’s’s seat of a B-25. These were the brief open years before the Cold War did away with the “old” Air Force. |

| I grew to awareness is a narrow and unique slice of time. Someone a few years older than I am will tend to see our world of today from the perspective of the depression and having actually participated in the Second World War. Someone a few years younger will tend to see the world from the experience of having grown up in a global, technologically “driven” consumer society. In the brief period between 1945 and 1950, the U.S. experienced a vast social transformation. I was able to witness this for I grew up in a part of that society that had already seen, and even created, major aspects of this new economy with one major exception: in the world I grew up in, it was not about money - it was about mission. Money was a tool, like a screw driver or a global communications network. Money was not the end, it was the means [link: the tool that became a god]. Because I saw this transformation, it is natural for me to “see” the transformation ahead. The great change is not behind us - it is ahead. The magnitude of it is orders of magnitude greater than our society has experienced in the last 50 years. It will be global, it will be knowledge-based, it will employ network architecture and the great value add will be design. Not just the design of products. The design of everything from organization to society and, ultimately, humanity itself. We are now creating, by design or default, the circumstances that will drive our own evolution. |

| I decided to become an architect when I was 11 years old [link: matt taylor history 1949]. From that moment on, architecture became and has remained the integrating practice of my life. My idea of architectural practice [link: mt sfia thesis], however, is much broader than what has become the norm in our society. My jr. high and high school years were spend in a boarding military school [link: palo alto military academy] and a Jesuit prep school [link: st ignatius high], respectively. Again, intentional communities with a focus far removed from that of the general society of the time. I never finished my last year of high school nor did I go to collage from reasons that are both amusing and saddening [link: the [professor of architecture 1956]. In the summers, during my high school years, I worked on a ranch in the Trinity Alps [link: coffee creek ranch] - another community [link: matt taylor history 1955]. After a brief period of work in architectural offices, while still living at home, I spend time at Taliesin [link frank lloyd wright school of architecture taliesin] the home and workplace of Frank Lloyd Wright [link: taliesin return 2000], a mission focused, intentional community if there ever was one. I was in my early 20s before I “got out” into the regular world and it was a shock indeed. I could not figure out why people did what they did, what motivated them and how it was that they saw life and work. I could not understand how they could use technology as they did not understanding it nor having thought about the consequences of its use [link: the monkey’s paw]. Although I have learned to navigate this world and even influence it to some degree, there is a part of me that still cannot relate to it. It is as if I am an alien, not born here and just visiting, I was able, because of this mix of experiences, to see a huge transformation take place from the society of the early 40s to that of the 50s. When I entered school, the U.S. was still, technically an agrarian society. 40% of the houses did not have indoor plumbing, milk came in little bottles delivered often by horse drawn carts, an ice box was really an ice box usually located on the back porch - the ice was also delivered - a trip across the country by car was a notable experience and usually netted six or more flat tires. You carried a water bag on the front to get over the large mountains for the car inevitably steamed over. I remember the introduction of Wonder Bread, penicillin, pressure cookers, TV and network television. Traveling from base to base about every two or three years educated me to the huge differences in cultures to be found in the U.S. let alone other nations. I saw this world and interacted with it from a distance. I was not part of it for the community I was a part, as a son of a Air Force officer, was elite, did not struggle financially and, as before mentioned, was steeped in a global world view and the employment of technology to accomplish a critical mission. All the communities I spent my time in were meritocracies and work and life was highly integrated. These were alternative communities. Each had a long tradition behind them and a forward looking agenda. They were purposeful. My mother was a humanist, my natural father a builder, my grandfather a master mechanic [link: tom richards master mechanic] and my step father a pilot. Until I got out into the larger world, it never occurred to me that these things can be seen as anything but aspects of one thing. It never occurred to me that anyone would work “for” money and not what they loved to do and believed in passionately. I was raised to respect technology, to understand that if you neglected it, or used it poorly, it can “bite,” that it had its own nature and that it was rapidly becoming the driving force of a transforming global society. I was born at the end of the depression yet grew up in an early facsimile of the world that is just now coming into being. I had an extraordinary formal education until it stopped and I had to take that task on myself - this means that I wrote my own curriculum and thereby ranged over a far boarder scope of subjects than is usual and did this in two important ways. First, I did it in depth in most of the subjects I studied and second, I always studied in real-time relationship to the work which I was doing at any given time. For example, in New York when I was given my first multimillion dollar project as project engineer, in 1964, I was too young by at least a decade and short at least one degree if not two. I had to acquire a broad understanding of a number of engineering disciplines as fast as the work progressed - I was pouring 220 cubic yards of structural concrete every day while studying the science of it every night. Added to concrete was electrical, plumbing, HVAV and so on. My own work, as it progressed over the years, cut across traditional fields: architecture, construction, development, product design, graphics, manufacturing, corporate management, facilitation and consulting, teaching, futurism, invention and entrepreneuring [link: matt taylor resume]. This work experience focused my educational experience and does so to this day. I did not indulge in all these different fields of work for casual or superficial reasons. I wanted to build a certain kind of architecture from the beginning. I found that once I mastered one field it inevitably opened a new set of questions that lead to another. |

| It is from the totality of this work experience that I view technology and its potential. In the realm of computer, information and multimedia - all media is multi-media - from a pencil to a computer to interactive media to a global network. It seems to me our society has been provided a great box of tools. Too often these tools have been configured and used in a way that places them on the wrong side of the variety equation. They amplify when they should attenuate. Too much of work, today, has become responding to what others are responding to with no resultant contribution to either collaboration, productivity or sanity. When you consider how the U.S. ran a global logistics system during WWII with typewriters, carbon paper, telephones and telegraph; when you look at how Frank Lloyd Wright build several houses at a time [link: what makes an usonian an usonian] at various part of the country, with the same tools and train travel; and then you compare what we do today with the tools we have and considering the difficulty of accomplishing work - then it is reasonable to question if we are applying this wondrous capacity well and in the right places. No question that our world could not run as it does without the broad application of computer, information and multimedia technology distributed by the internet. Yet, I believe we are far from netting the real potential and value of these capabilities outside of the realm of consuming. We certainly are not happier than the world I grew up in and time will judge if - net out - we are actually more productive in the sense of creating and sustaining human quality. GMP may turn out to be a poor indicator of economic value [link: 12 aspects of an upsidedown economy].We are mired in confused standards, exploitative and often insanely false competition, too much focus on the technology itself rather than the work processes it supports and a fixation on the isolated only partially integrated software package called the “application.” |

| There is an old saying “don’t look a gift horse in the mouth” and for someone who was excited about the introduction of the ball point pen (it typically leaked and stained your shirt pocket but was nevertheless a status symbol) and who spent many years laboring over drafting tables without air conditioning, I certainly appreciate the technology I am using to publish this Paper. However, My sense is that we have used a great deal of genius to automate the 19th Century rather than understand and adequately support knowledge-work in all of its ramifications including the fact that, in the near future, design will be the last bastion of human value-add. I expect nearly everything else to be made marginal by ubiquitous knowledge, automation, machine intelligence and the global economy. And, this is just the current circumstance of the near future. Advances in genetics, computers and nanotechnology will quickly - much faster than generally understood - create machines and human augmentation that will completely alter the equation of human labor and even the role of humans in the economy. By design, I mean more than the design of products, although the handwriting is certainly on the wall, in this regard, when you look at the recent successes of the Apple Corporation. I mean the design of everything including organizational design and enterprise architectures of all sorts. Even in the realm of design, machines - first as augmentation - will soon be serious competitors except for the very best human designers. Only the very educated, wise and imaginative will prevail. These trends have many serious ramifications. Many are surely good. Some have massive downsides. “Disruptive technology” is about to take on a whole new meaning. How long? 25 years with many revolutions within that period each on the scale and scope of the last 50 years. |

| So we embrace a paradox. I am pushing for a far more robust use of technology in the realm of human augmentation. In doing so, we face the specter of the greatest amount of change in the shortest time period in the known history of civilization. The safe path out of this is to use augmentation well so that we can stay requisite with the changes we ourselves are making. And, we must bring humanity and all life along with us. The record of the recent past, in this regard, can cause you to be a pessimist or an optimist depending on your disposition. As a designer, I am optimist who takes a very pessimistic view of our present situation and the processes that generate this condition [link: a future by...]. It is said that we humans will never understand our own cognitive processes. I disagree. Not only will we do this with technology we will do it with the technology of the mind itself. The designer’s mind, and experience, approached in a deliberately self-aware way, opens the door to human cognition. This is because to design is to use the mind as a tool. In the 60s, I built a model of the human mind employing Black Box Theory. Observation of how people worked, introspection of my own processes and studying the acknowledged great innovators (to the extent that they have been documented) produced a provisional model. This model was remarkably predictive and has held up well for 40 years. It provided me a platform that allowed systematic testing in the arenas of creative thinking, collaboration and process management. For the last 25 years we have been embedding this model in our processes, technology and environments and refining it by facilitating human creativity. So, with paradox in mind, here goes... |

| The “application” focus is wrong. Writing, drawing, filing are not applications, they are tools needed to accomplish most work. An application is conceiving, illustrating, pricing, building and managing a building over a century - not writing, calculating, drawing and so on. Programs have made great strides toward compatibility and integration of a sort. But think of this: how many word processors do you have on your computer? How different are they in their command structure and embedded process? How much is your work process actually determined by the tool? There is no such thing as neutral technology - every technology is embedded thought and imposes a point of view and process - good or bad, useful or not. Can you configure this tool kit to facilitate and augment your work, in the way that you work - or, are you in reality “forcing” your cognitive processes to conform to the environment of the machine? The interface metaphors used today, while useful entry level guides, are ultimately all wrong. They are based on pre-augmentation (and advanced technology) experience. They pull you back into this old realm with all of its cognitive implications. We have a desk top? When was the last time you saw a desk that truly worked? Video? Is this how you “see?” The typewriter, camera, motion picture camera and spreadsheet are still with us - all creatures of long gone technology limitations. Do you know that clay tablets thousands of years old had spread sheets? How would you design the process if you started with a modern computer and no assumptions or installed base? How would you build the computer if the work packages were not based on pre-computer assumptions? What could a smart human and a smart computer do if they could collaborate? Of what value are virtual conferences of talking heads? How well can kinesthetic thinkers do sitting at a table? What does the shape and the size of the table do to the process and interaction of the meeting? How about the different sensitivities that individuals have to light, sound and texture and the effects these have on their cognition? What is the memory-cognitive consequence of looking up or down, left or right and how does our technologies and architecture impose these “viewpoints” without awareness, rhyme or reason? When in the flow of creative work, what is the risk and consequences when attention has to be turned to the requirements of technology and away from the requirements of thought? |

| Does your personal (?!) computer learn from you - observe your habits and anticipate your needs and adjust itself accordingly? Impossible? I wonder. I think there are numerous ways this can be done and that their necessary algorithms can supported by current technology. more to come |

Because of limits imposed by Dreamweaver, in regards to the length of documents in frames, I had to split this document into three parts - please go to part two of this Paper.

link: idiap presentation - part two

Part Two includes:

a brief description of the Taylor Method; how we use technology; how we know it works; and, what we have learned.

Part Three includes:

some interesting questions; comments on As We May Think, my final thoughts and Postscript. |

|

|

|

Matt Taylor

Montreux

November 24, 2005

Elsewhere

December 22, 2005

SolutionBox voice of this document:

VISION • STRATEGY • EVALUATE

|

posted: November 24, 2005

revised: January 6, 2006

• 20051124.342810.mt • 20051222.338124.mt •

• 20051224.239871.mt • 20051226.222200.mt •

• 20051228.567581.mt • 20060105.562312.mt •

• 20060106.002341.mt •

(note: this document is about 85% finished)

Copyright© Matt Taylor 2005, 2006 |

|

|